Prevalence of Homelessness in Greater London. 10,053 people seen rough sleeping in 2022/23 [link].

Night shelters. People who would otherwise sleep on the streets can usually get into night shelters for free, but capacity is limited, sleeping space is shared, some shelters are only open during the winter months and there are eligibility criteria that need to be met. There are currently around 390 winter shelter rooms in London [link].

Hostels and related. Hostels are not always free and may require a referral from a charity, but generally offer more space and independence. This project aims to make it easier to make donations that are directly used for hostels and related type of accommodations. There are currently around 12068 bed spaces in hostels and related temporary accomodations [link].

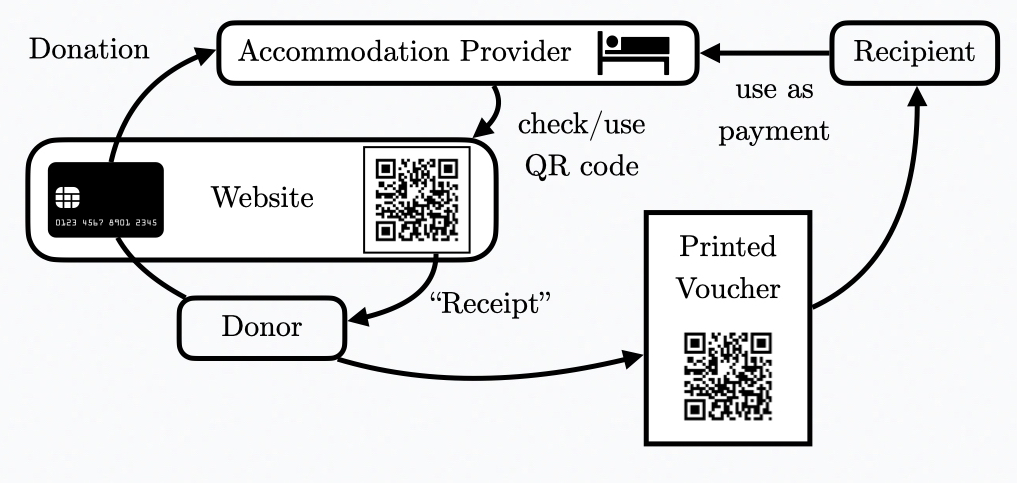

https://nightvoucher.co.uk?id=abc123&pw=cde456).Trusted accommodation providers. Accommodation providers do not need to trust the website, as the received donations indicate a code that can be found on the access website to confirm which donation it links to. The accommodation providers do not receive the access link with the donation, but accommodation providers need to be trusted to provide services that are paid for in the dedicated donation.

Importance of Face-to-Face Interactions. While it is possible to donate directly to somes accommodation providers (e.g., sponsoring young homeless people [link]), both donors and recipients alike deeply benefit from a more human-to-human interaction (moral support and goodwill can go a long way).

Dedicated donations. While giving cash is always a possibility and may be the best choice, accommodation costs for multiple days/weeks/months can be substantial and without knowing the person very well it harbours the risk that the money may be used for things that further the problem rather than helping out of it. Thus, to overcome reluctance on the side of donors (especially for larger sums) and to guide recipients towards accommodation, this project aims to make it easier to make dedicated donations via vouchers.

Intention of the project. It is not meant to solve all problems, but in the best case it may inspire more people to give more money, more money may go towards accommodation and more opportunities may be created for positive interactions; all of which may help a person to find a safe place to sleep and try to find a way out of homelessness. The goal is to keep the project simple enough to not require any donations for the project itself and to only accept volunteer work and partnerships that are directly used towards the project, i.e., anything that could go directly towards providing people with a safe bed should go towards that.

Cooper, V., & McCulloch, D. (2023). Homelessness and mortality: an extraordinary or unextraordinary phenomenon?. Mortality, 28(2), 220-235. [link]

This article explores the ways in which homelessness and mortality are constructed as an unpreventable phenomenon, not deserving of any meaningful political intervention. Drawing on the conceptual framework of ‘organised abandonment’, we argue that the invisibility of homeless people in death can be linked to their invisibility

Killing with your kindness: anti-homelessness as a form of organised abandonmentControversial Poster Campaigns in the UK

There have been some controversial campaigns in the UK with slogans like “killing with kindness” [link] that were briefly adopted by some local authorities such as:

Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (2022). Ending Rough Sleeping For Good, September 2022. London: DLUHC. [link]

There is not just a moral case for action. Ending rough sleeping is the right thing to do to ease the strain on health and other public services and to enable everyone in a community, including those who are homeless, to feel safe and for our cities, towns and high streets to prosper. Support and services for people who experience rough sleeping come at significant cost, and reducing rough sleeping therefore reduces that cost. It will also deliver benefits across the system, such as through reducing reoffending.

We know that having a suitable accommodation offer is a vital first step in bringing someone off the streets and helping them access the appropriate support – which was illustrated by the great progress made during the pandemic. During this time, we saw how an increased focus on single-room accommodation was not only successful in preventing the spread of COVID-19, it also provided people withthe space, dignity and support they needed to move away from rough sleeping.

Centre for social justice (2017). Housing-led solutions to rough sleeping and homelessness. Housing first. [link]

There is overwhelming evidence to support the use of Housing First, which provides stable, independent homes alongside coordinated, wrap-around, personalised support to homeless people, as a housing solution. Evidence also shows that over the course of a Parliament the implementation of Housing First would be cost neutral. This is a smart upfront investment that will save the Government money and, more importantly, save lives. The Housing First model provides individuals with a stable independent home, combined with the personalised support they need to gain access to mental health services, drug and alcohol support, in addition to training for employment when and if they are ready.

Bowpitt, G., & Kaur, K. (2018). No way out: a study of persistent rough sleeping in Nottingham. [link]

We are often asked why rough sleepers reject help when it is offered, and the conclusion people frequently draw is that persistent rough sleepers are sleeping rough out of choice. However, the truth is that rough sleeping is rarely the only problem that persistent rough sleepers face. Often they manifest an accentuated intensity of complex needs and negative life experiences of domestic violence and personal victimisation. Many of them carry a baggage of negative risk assessments arising from past anti-social behaviour, accumulated indebtedness, eviction, rejection, disqualification and disentitlement that may bar them from whatever accommodation and other services might be on offer.

Bramley, G & Fitzpatrick, S 2017, 'Homelessness in the UK: Who is most at risk?', Housing Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 96-116. [link]

[It] has made clear that, in the UK at least, homelessness is not randomly distributed across the population, but rather the odds of experiencing it are systematically structured around a set of identifiable individual, social and structural factors, most of which, it should be emphasized, are outside the control of those directly affected.

Hwang, S. W., & Burns, T. (2014). Health interventions for people who are homeless. The Lancet, 384(9953), 1541-1547. [link]

Housing First, with immediate provision of housing in independent units with support, improves outcomes for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Many different types of interventions, including case management, are effective in the reduction of substance misuse.

Fallaize, R., Seale, J. V., Mortin, C., Armstrong, L., & Lovegrove, J. A. (2017). Dietary intake, nutritional status and mental wellbeing of homeless adults in Reading, UK. British Journal of Nutrition, 118(9), 707-714. [link]

The findings of this study highlight the vulnerability of homeless adults in Reading, who have reduced mental wellbeing, a higher risk of [cardiovascular disease] and a poorer dietary intake compared with the housed population.

Fitzpatrick, S., Bramley, G., & Johnsen, S. (2013). Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities. Urban Studies, 50(1), 148-168. [link]

People have experienced [multiple exclusion homelessness (MEH)] if they have been ‘homeless’ (including experience of temporary/unsuitable accommodation as well as sleeping rough) and have also experienced one or more of the following other ‘domains’ of deep social exclusion: ‘institutional care’ (prison, local authority care, mental health hospitals or wards); ‘substance misuse’ (drug, alcohol, solvent or gas misuse); or participation in ‘street culture activities’ (begging, street drinking, ‘survival’ shoplifting or sex work).

Sequencing analysis revealed that substance misuse and mental health issues tended to arise early in MEH pathways, consistent with the argument that childhood trauma can undermine coping mechanisms in young adulthood, with potentially long-term consequences for health, wellbeing and social functioning. Homelessness, street lifestyles and adverse life events typically occur later in these pathways, strongly implying that these experiences are more likely to be consequences than originating generative causes of deep exclusion.

Baxter, A. J., Tweed, E. J., Katikireddi, S. V., & Thomson, H. (2019). Effects of Housing First approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Epidemiol Community Health, 73(5), 379-387. [link]

Lee, B. A., Tyler, K. A., & Wright, J. D. (2010). The new homelessness revisited. Annual review of sociology, 36, 501-521. [link]

Because many homeless face challenges in health and other life domains, it is tempting to treat any deficits in these areas (e.g., mental illness) as antecedents of homelessness. But deficits can just as readily be outcomes produced or exacerbated by street and shelter existence.

Homeless people suffer from reduced life chances, experiencing disadvantages in material well-being (e.g., income and benefits), physical and mental health, life expectancy, and personal safety.

Coping strategies employed by the homeless include shelter and service usage, wage labor, shadow work, reliance on social ties, identity management, and political mobilization and activism.

Jones, A., & Pleace, N. (2010). A Review of Single Homelessness in the UK 2000-2010. [link]

Single homeless people interviewed for this review reported that, whilst they had been grateful and relieved to have secured hostel accommodation, they could be frustrated at the time it had taken (or was taking) to find appropriate permanent housing. They could also find hostel life difficult and stigmatizing.

Quilgars, D., Johnsen, S., & Pleace, N. (2008). Youth Homelessness in the UK: a Decade of Progress?. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [link]

Raoult, D., Foucault, C., & Brouqui, P. (2001). Infections in the homeless. The Lancet infectious diseases, 1(2), 77-84. [link]

It is currently in its infancy and merely the idea of one computer science researcher (hopefully soon more) who will try their best to make this a reality, but any help would certainly speed up the process and increase chances of success. Thus, do not hesitate to get in touch with michael@nightvoucher.org.uk if you think this project could be helpful. The basic idea is to provide the technical platform first that can be used for dedicated donations before building explicit partnerships with charities.

Note: The views and opinions expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of their employers.